What the data keeps whispering...

Why the numbers say fashion’s most sustainable future is “less.”

I spend a lot of time reading headlines, industry briefings, research papers, and policy updates. Hundreds each month. Taken alone, they feel small. But stacked together, they start to hum with the same refrain.

The numbers don’t shout.

They whisper.

And what they whisper about fashion isn’t subtle at all: the system is moving faster, producing more, and wearing out sooner.

The whispers of scale

“Global clothing production has doubled since 2000 while the average consumer buys 60% more clothes and keeps them half as long,” McKinsey & Company reported in its 2016 State of Fashion briefing. “It’s not a moral problem,” one McKinsey analyst told me recently. “It’s a throughput problem. More in, faster out.”

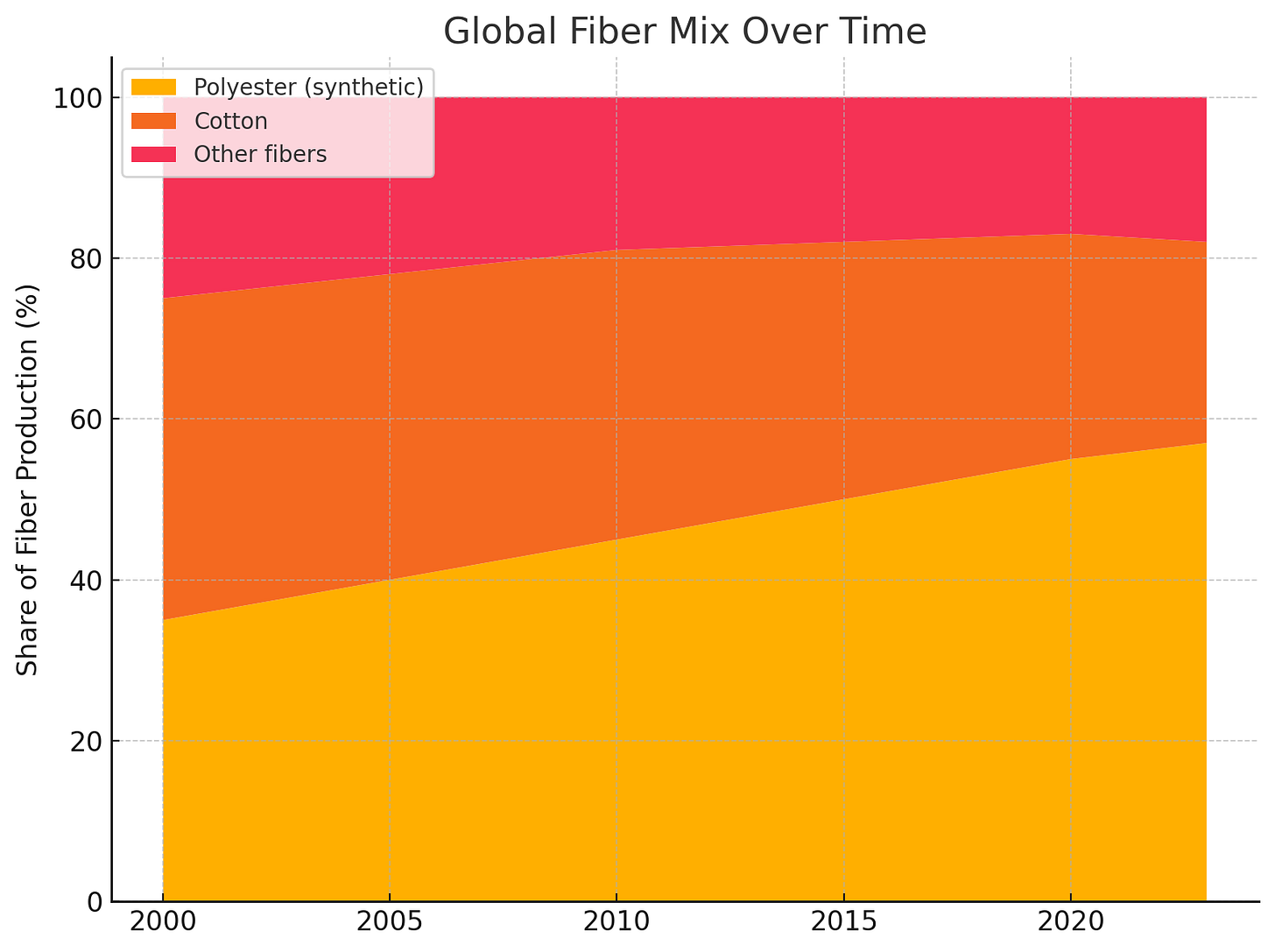

UNEP data puts a sharper edge on it: 60% of clothing today is made from synthetic fibres, essentially plastic. As Elisa Tonda, head of UNEP’s Consumption and Production Unit, warned in a 2021 press statement: “With every wash, these materials shed microfibres that escape treatment plants and end up in our rivers, lakes and oceans.”

The European Environment Agency estimates the toll: 200,000 to 500,000 tonnes of textile microplastics enter oceans each year.

Meanwhile, volume keeps climbing. According to Textile Exchange’s Preferred Fiber & Materials Market Report 2024, global fiber production hit 124 million tonnes in 2023. Polyester alone makes up more than half. “Volume is the headline,” one Textile Exchange researcher told me, “but synthetics are the subhead.”

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation translates this into a picture: “Every second, a truckload of textiles is landfilled or burned.” Less than 1% of material is recycled into new clothes.

The oxymoron we can’t shake

Earlier this summer, Down to Earth published a line that has hovered over my notes ever since: “Sustainable fashion is an oxymoron.”

The point wasn’t that better practices don’t matter. It was that scale that showed improvement. Even responsible production, multiplied by billions of garments, cannot yield sustainability.

As the EU Environment Commissioner put it, “We have to react” to the fashion industry’s outsized pressure on natural resources, truly a systems-level issue

When I track what I actually wear, not what I admire, the pattern is clear: linen wide-legs, a black silk slip, soft tees, my Romanian ie that makes any day ceremonial. These are my workhorses. The rest are decoys.

Economists call this “utilization.” I call it impact-per-wear: the footprint of a garment spread across the number of good days it delivers.

McKinsey makes the same point in a different language: “Shortening wear-life is the problem engine. If we lengthen it, we change the math.”

Why “better materials” won’t save us

Brands have raced to adopt recycled polyester, often from bottles. But as Vogue Business has reported, bottle-to-shirt recycling breaks a closed loop and still sheds microfibres.

“The uncomfortable throughline is overproduction,” said one researcher at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation when we spoke. “Recycling and design matter, but without volume reduction, they’re a band-aid.”

Even the Foundation’s own roadmaps concede this: design for recycling is necessary, but insufficient.

Beyond carbon and waste, there’s psychology. “The more we chase status and image through material goods, the less content we tend to be,” said Tim Kasser, psychologist and co-author of decades of materialism research, in a Journal of Personality and Social Psychology meta-analysis.

That resonates with my mornings. When my closet is small but right, I decide less and do more.

The numbers don’t tell us to abandon beauty. They tell us to abandon duplicates of the same story.

Here’s what I hear them whispering:

Buy less, on purpose. If you can’t picture 30 wears, don’t bring it home.

Prefer fibres that behave in life. Wash lightly, shed less.

Mend first. Spare buttons in a jar, a darning mushroom on the shelf, a tailor you know by name.

Rotate by season, not trend. Clothes that migrate across contexts earn their keep.

Exit with dignity. Resell, swap, recycle, rag. Landfill last.

As the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) now makes clear, durability, repairability, and recyclability are no longer optional; they’re required for textiles entering the EU market. By 2030, all textile products must be durable, repairable, and recyclable.

Social media’s echo

The data tells one story, but social media amplifies it. TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube don’t just reflect trends; they accelerate them.

According to The State News, TikTok paired with fast e-commerce “caused trend cycles to speed up… things can quickly lose their sparkle once enough people have gotten ahold of it.”

We’re no longer on a bi-annual schedule. Research shows fast fashion now runs 52 trend cycles per year, a new style every week.

TikTok is the chief conductor. Micro-trends, think jelly-donut blush or “mob wife aesthetic”, flare into virality and vanish just as fast. Aquent reports that these trends, amplified through TikTok’s algorithm and dupe culture, have “created even shorter trend cycles” and driven overconsumption. 70% of ‘dupe’ shoppers are on TikTok. According to one fashion commentator, what used to take years now rises and falls in weeks or days.

This relentless churn breeds fatigue. As observed by Vault, “trends rise and deplete in the blink of an eye,” undermining personal style and authenticity. Even Vogue Business notes: as micro-trend fatigue grows, brands will need to shift toward cultural “vibes” that feel authentic rather than formulaic.

Universities have become fast-fashion catwalks. The Guardian reports that TikTok aesthetics like #RushTok drive back-to-school collections by Shein, Skims, and Asos—marketing built on campus virality.

Even sustainability-minded Gen Z shows the tension: NY Post found that despite pledges to buy sustainable, members of Gen Z still heavily shop fast-fashion due to social trends, social media influence, and budget constraints, highlighting the gap between ideals and impulse.

People behind the pieces

Fashion’s whispers aren’t just about fibers or waste, they’re about livelihoods. Around 430 million people, roughly 12% of the global workforce, depend on fashion for income. In India, textiles employ more than 35 million people, making it the country’s second-largest source of jobs after agriculture. In Bangladesh, the story is deeply gendered: 2.7 million women, more than half of the garment workforce, stitch together not just clothes but economic survival for their families. Even in the United States, fashion still supports nearly 1.9 million jobs, most in retail.

When we talk about slowing production and extending the life of garments, these are the lives in the balance. The numbers whisper not just about consumption, but about the people who cut, sew, dye, and finish our clothes.

Put the signals together: waste, carbon, microplastics, endless trend churn, millions of jobs, and the pattern is obvious: fashion runs too fast, too big, too disposable.

The data doesn’t point to slogans or silver bullets. It points to one thing: fewer pieces, worn longer.

Any vision of “sustainable fashion” that ignores them isn’t sustainable at all.

I really hope you're enjoying The Sustainability Pulse, my weekly newsletter looking at sustainability in the fashion industry. If you find the tips and insights useful, please share these articles to help spread the word.